The project I spent a tenth of my life on was just cancelled — none of our work belongs to us

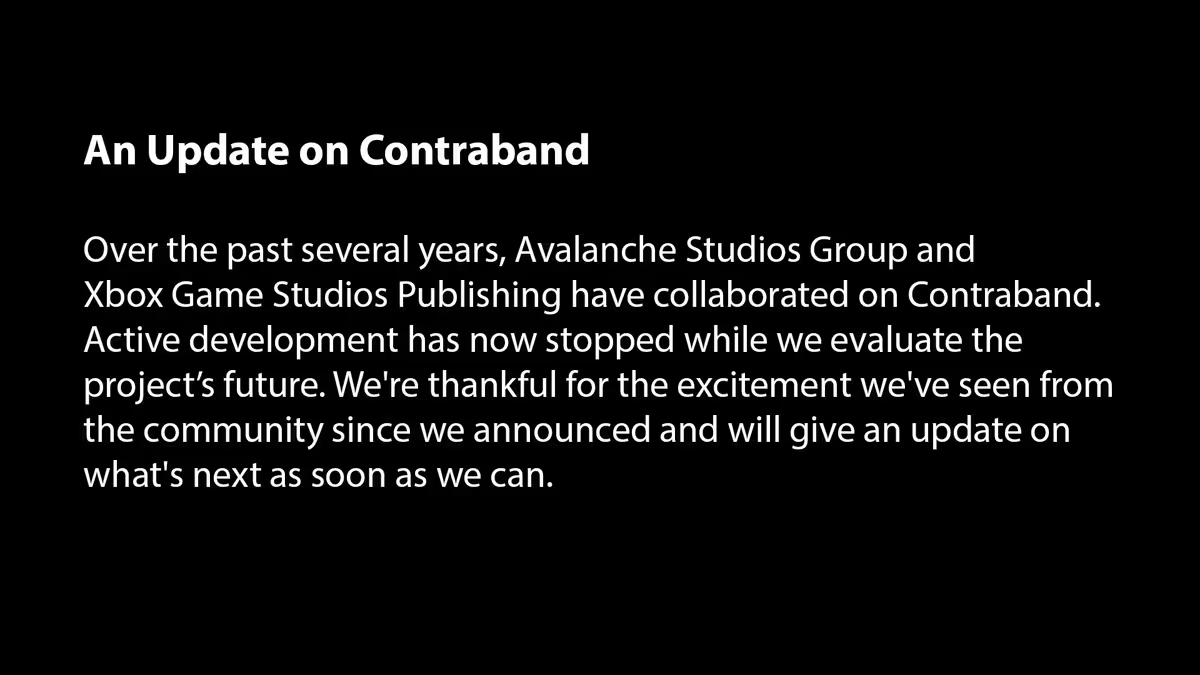

Two days ago, it was announced that Xbox are cancelling Contraband, the project I worked on for the three years and seven months I spent at Avalanche Studios—around 11% of my life, at time of writing, and about half of my career in the games industry.

Two days ago, it was announced that Xbox are cancelling Contraband, the project I worked on for the three years and seven months I spent at Avalanche Studios—around 11% of my life, at time of writing, and about half of my career in the games industry.

I'd be lying if I said the news were entirely unexpected; without going into details, production on Contraband was far from smooth sailing. But it still sucks to see something you and over a hundred other people invested time and energy—productive years of our lives that can't be reclaimed—on a project that is now unlikely to ever see the light of day.

I'm definitely not the worst affected by this. On a practical level, I don't work at Avalanche anymore, so this cancellation doesn't pose a risk to my job. The same can't be said for the developers—many of whom I consider friends—who don't know if they'll still have a job in the near future. I hope the leadership at Avalanche had a good plan prepared for this eventuality, and I wish the current union club board the best of luck in negotiating any potential layoffs with leadership. The recently signed collective bargaining agreement will hopefully be helpful.

On an emotional level, I've always retained what I consider a healthy distance from the projects I work on, and my function in a game team is less about creating the game itself as it is about supporting the people who are. But I know people who were putting their hearts and souls into this game. Some people have invested more years of their lives into Contraband than I've spent in the industry.

For those people, my former colleagues and teammates, I am so sorry.

What angers me the most is no one will see what we made. Designers, artists, animators, programmers, writers, sound designers—with few exceptions, none of these people will be allowed to show off their work. Because even though every game ever made is the product of the effort and creative energy of every single person that worked on it, most of us don't own any of our work.

It doesn't have to be this way. If you read last month's media roundup post, you might recall the two posts by Ryan K. Rigney—about the deprofessionalization of the games industry and its possible future—I wrote about there. In an industry where studios are owned by the developers, not only would the rewards of success be more equally distributed; in the event of failure, each person would still be free to bring their work with them, to talk about and show to others as they see fit.

The cancellation of Contraband is yet another reminder that this industry could be better. If you want things to change, I suggest getting involved in your local union. Not because they're perfect—they definitely aren't—but because they're one of the best ways we have for organizing workers and applying collective power to influence companies.